Amnesic Displacements, Times & Spaces

closeThe presence of time looms over Man from the moment when he is faced with the immanent transience of his physical environment. Time is simultaneously a personal, existential and subjective experience, as well as something that connects the individual to larger, natural, social forces, among many unfathomable others. The human need to understand himself belonging to a continuum that makes his existence intelligible is expressed by the desire to synchronize his periodic events (celebrations, holidays, etc.) to the cyclical character of the movements of nature and of the celestial bodies (solstices, moon phases, seasons, etc.), as well as to a genealogy of past events that shape a common history. Minutes and seconds are not only intervals of time, but also angular measurements of distances on the earth's surface that accurately determine Man’s position in territory. Time shelters and locates us. It is a means to measure the relative interval between sequences of events, analogous to what distance is to the positions of bodies in space.1

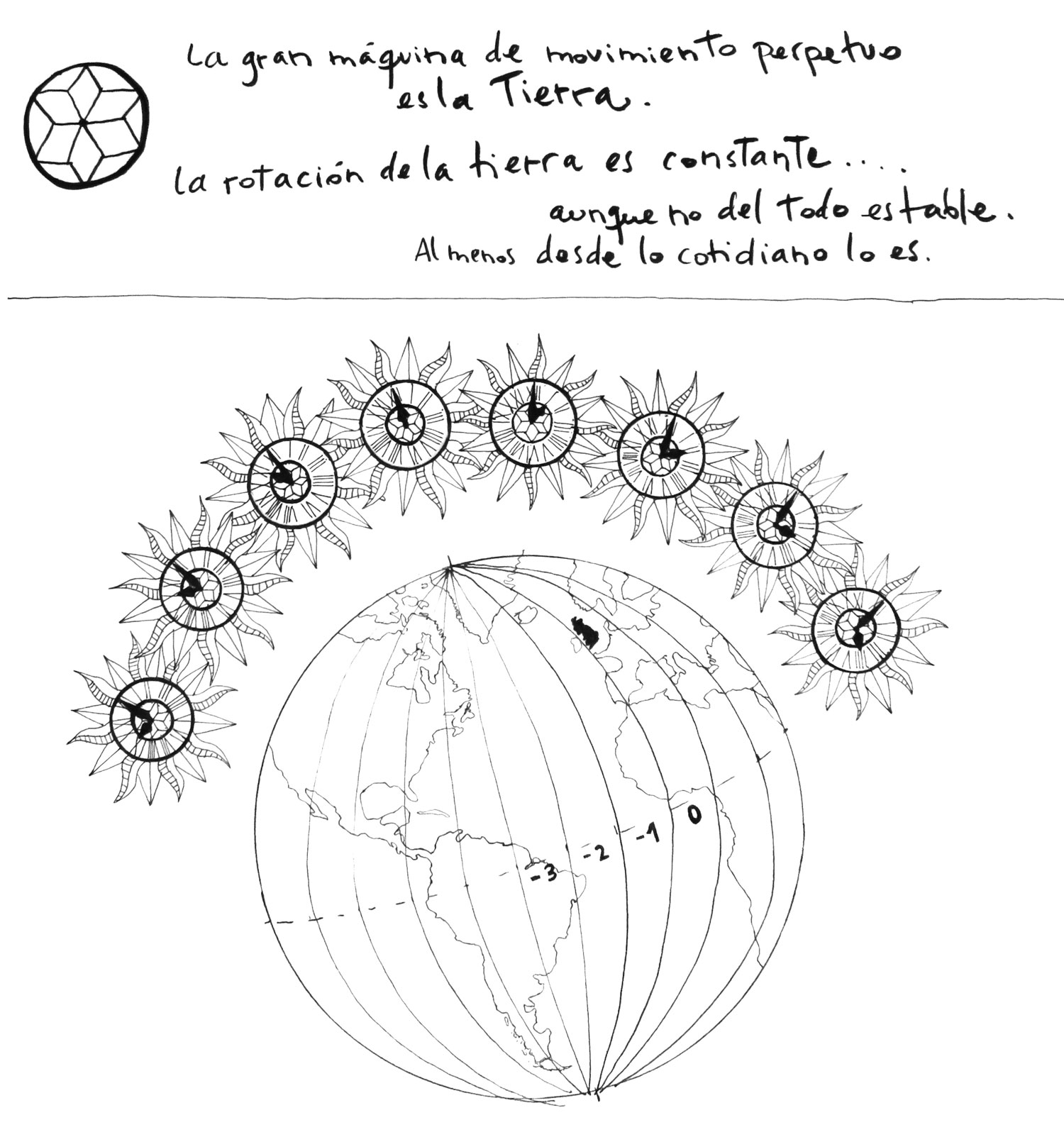

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Division of the terrestrial globe into 24 time zones. Drawing by Pilar Quinteros, 2017.

The change of position in time is what we understand as movement, a concept that combines the inseparability of the notions of space and time. The possibility of an increasingly faster displacement through territory was one of the main boosters for a radical change in the contemporary conception of time. The factor that consummated this was the advent of rail transport, consequential of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. The speed of this collective transportation allowed the crossing of several municipalities with distinct local hours, each one empirically based on the position of the Sun. When going through a myriad of local times, the constant readjustment of clocks became necessary, as any mistake or imprecision could cause delays or accidents. Increasing the efficiency and safety of this process made it urgent to create a shared benchmark for determining time. Thus, before any political or scientific conventions, railway companies were the first to implement Standard Time, instituting London as a reference from which all other time zones were calculated. After this convention, railway station watches acquired two groups of pointers, one marking the local time and the other showing the Railway Time. Gradually the ‘standard’ was imposed to the ‘local’ and in the second half of the nineteenth century the first model for international civil-time was established with the formalization of Greenwich as the prime meridian from which the earth's surface was divided into 24 time zones.

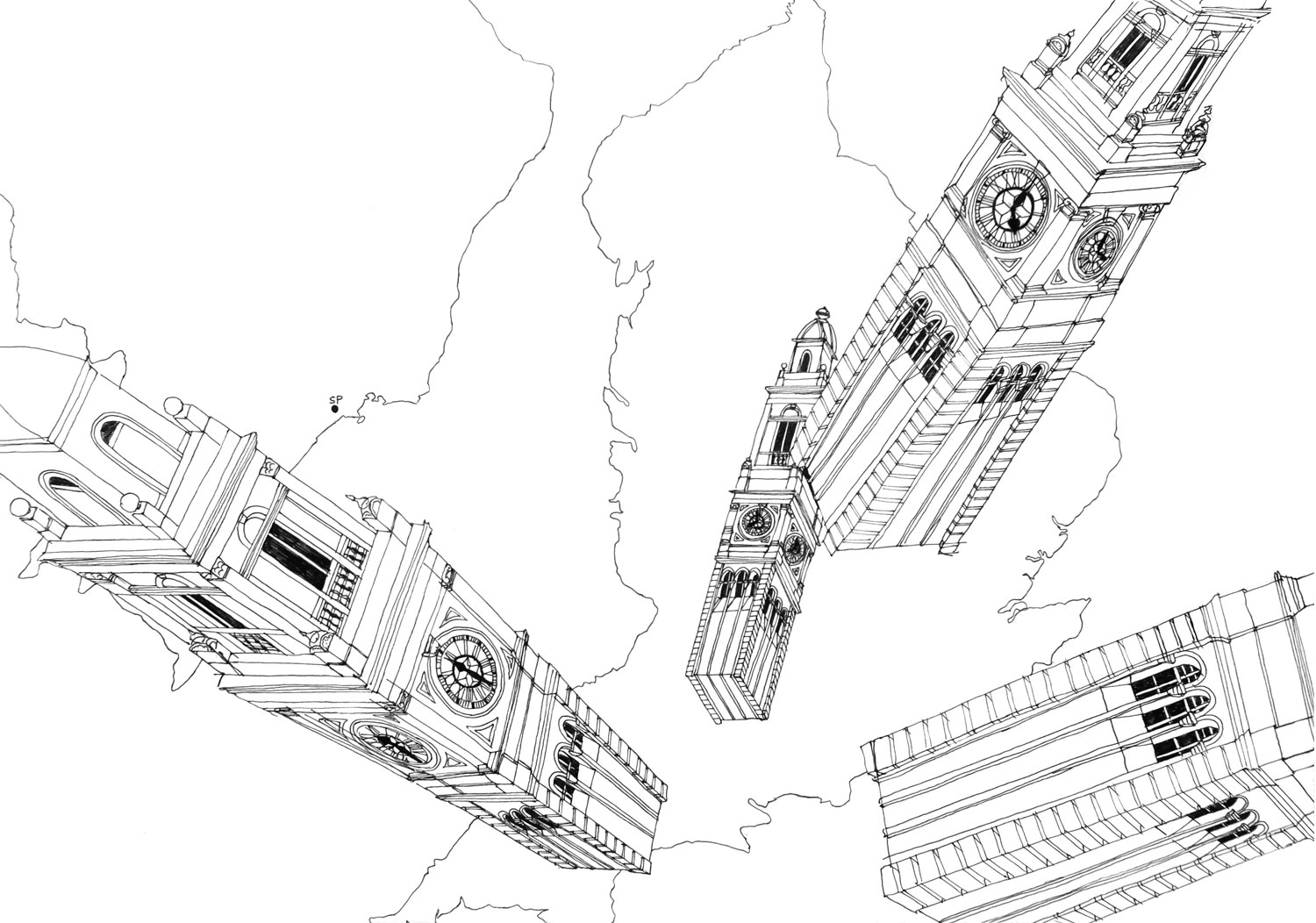

Clock towers from Luz Station, São Paulo. Drawing by Pilar Quinteros, 2017.

The implementation of this abstract convention in parallel to the worldwide diffusion of rail transport signalled the arrival of another global temporality associated with new forms of movement that carried hegemonic and Eurocentric ideals of modernity, reason and progress. This spatiotemporal colonization was imposed both by the transfiguration of abstract notions of time-space and also by a direct action over the built environment. Such physical intervention was potentiated by the ease of manufacture and global transportation of prefabricated industrial parts, ranging from small components to structural and ornamental elements of large buildings. One of the most widespread and symptomatic symbols of this spatiotemporal transculturation process is the railway station’s clock tower. The notion of public time associated with the monumentality of the tower is a recurring feature in many cultures throughout the history of mankind. But the cyclopean presence of railway clock towers expressed another notion of time. One that subordinated all citizens to an automated existence of precision, uniformity and efficiency based on a ‘time economy’ and on a new ‘value of time’ which were strongly related to the uninterrupted flow of people and goods across the territory.2

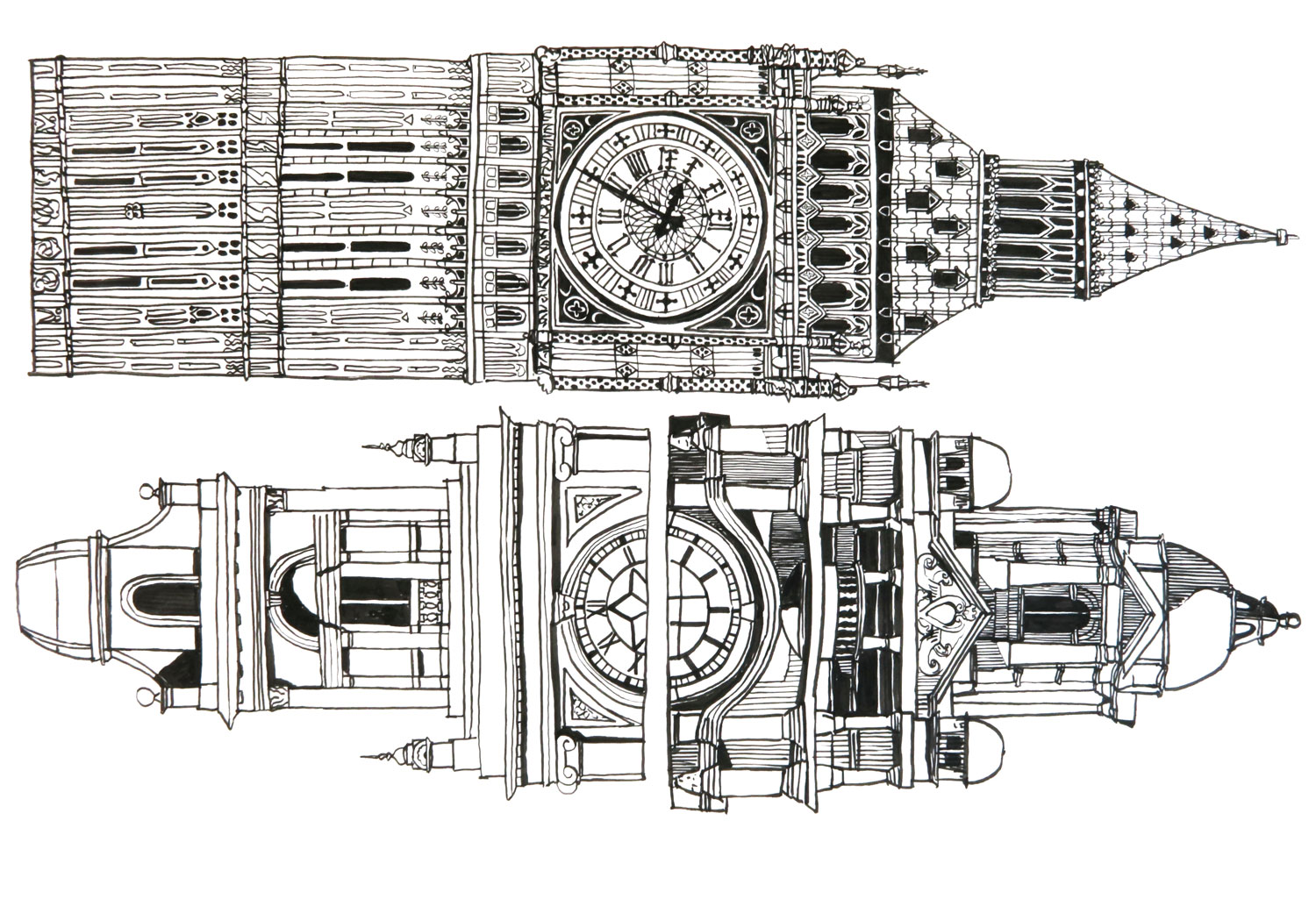

Above - Elizabeth Tower (Big Ben), Westminster Palace, London. Below - clock towers from Luz Station, São Paulo and Flinders Street Station, Melbourne, both designed by English architect Henry Drive. Drawing by Pilar Quinteros, 2017.

The prominent presence in the city of such clock towers seems to anticipate the latest conquered supremacy of time over space. Being unable to act directly upon abstract dimensions, Man shapes what is tangible, acting upon space as a means of controlling time.3 In this way, the city is not a fortuitous accumulation of disparate rhythms and velocities, but an environment that is structured in order to impose different temporalities upon distinct social constituencies. The optimization of the duration of citizens’ displacement, for example, is a key factor in the organization of urban space and in the social domination exerted by it. The control over the duration of dislocation within cities is one of the main mechanisms of socio-spatial segregation. This has evident manifestations in the territorial hierarchy expressed by the dichotomy between centre and periphery, by the oscillation of land prices, by the establishment of neighbourhoods with different time-space impediments of accessibility, among other examples. On the other hand, the acceleration of the pace of the city’s mutation, based on processes of incessant demolition and (re)construction, institutes a volatile public sphere that upholds a feeling of disposability of any physical structure as well as of the life of its inhabitants. Such fleeting spaces produce an amnesic time, incapable of apprehending the constant becoming, displacement and disappearance of its physical environment.

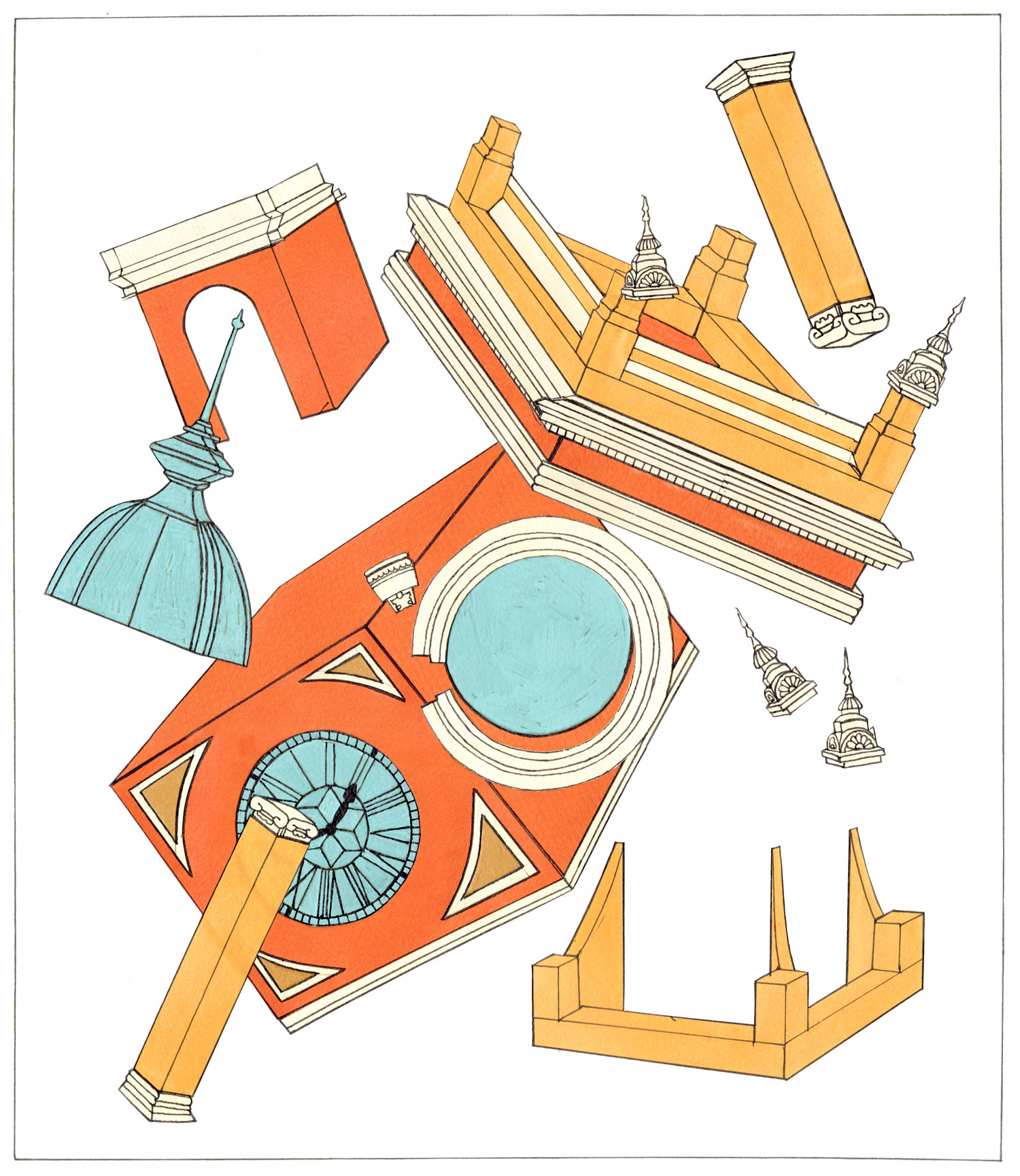

Clock tower from Luz Station, São Paulo. Drawing by Pilar Quinteros, 2017.

Curatorial text for SITU #6, Friends of Perpetual Movement by Pilar Quinteros, Galeria Leme, São Paulo.

-

Mario Radovan. On the Nature of Time, Rijeka University, Rijeka, Croatia, 2015.

-

John Durham Peters. “Calendar, Clock, Tower” in Deus in Machina, Fordham University Press, New York, USA, 2012.

-

Flávio Villaça. Reflexões Sobre as Cidades Brasileiras, Studio Nobel, São Paulo, Brazil, 2012, p.69.