Between Sign & Coordinate

closeBorn from the primary gesture of who signs a place or takes possession of it: two axes crossing each other at a right angle, that is, the very sign of the cross.

Lúcio Costa’s symbolic gesture, that marks the inception of his design for the capital city Brasilia, carries the ancient human need to locate oneself in the world. With the intersection of two axes in space, man establishes the starting point for the set of coordinates that locates and relates him to his surroundings. The geometric figure originated by this intersection, the cross, is one of the earliest symbols in human history. Since the Neolithic period, the use of different types of crosses indicates the different ways of being, physically and ideologically, in the world. To both horizontal axes (x, y) a vertical one (z) is intersected, related to the upright position of the human body. It not only establishes three-dimensional space, but also creates a symbolic bridge between the human and the divine, epitomised by the sky. The reciprocity between the understanding of the territory (ground) and of the cosmos (sky) has guided the discovery of ‘new worlds’, nurtured beliefs and located cities and buildings, shaping different modes of living. By connecting the points of the sky’s dotted grid, each civilization drew its own physiognomy, tracing a myriad of cosmic maps with the shared desire of further understanding where they were located and what was out-there. Through disparate drawings and interpretations, one finds a shared symbol that synthesizes this human yearning for a reference-point amidst the unknowable, a cross drawn by connecting four celestial bodies, the Southern Cross.

Opening of the road axes that define the pilot plan for Brasilia. Ground zero of the new capital of Brazil in 1957. Photo by Mario Fontenelle. Public Archive of the Federal District, Brazil.

The Southern Cross’ symbolic strength runs through different cultures and conceptions of astronomy, from the western to the aboriginal and indigenous of the southern hemisphere. In Quechua, one of the Inca languages, the Southern Cross is called Chakana, which is also the name of the Inca cross, a central symbol for pre-Columbian cultures. A squared and stepped cross with twelve corners, its geometry is entirely based on observations of celestial bodies and nature cycles. Its four sides represent the four directions and the four seasons, and each segment is divided into three steps symbolizing the worlds of Gods, men and the dead.

Geoglyph shaped as a Chakana only visible from an aerial perspective. Courtesy of LiMac.

While in most crosses the intersection point of both lines defines the basic-coordinate of man’s place in the world, in the Chakana this intersection does not exist, it is a circular void. In the Andean mythology the void at the heart of this cross represents the unknown, the unimaginable and the sacred. Hence, the Chakana’s symbolism and geometry seem to refuse the determinism of this basic-coordinate towards other notions of space-time. This way of understanding the human relationship to its world did not translate into an imprecision in the definition and planning of space. Several pre-Columbian settlements used orthogonal geometric grids both at the scale of the building and of the city, not very different from the ones we know today. But the pre-Columbian grid goes beyond the mere rational appropriation of space through geometry and mathematics. It is understood as being inserted within a larger logic established by nature and the cosmos. It is the means to establish a complete union between human life and culture, with nature and the divine. The notion of geometry synthesized in the Chakana’s sacred shape, traversed the daily life of these civilizations, ranging from the wider scale of the urban and architectural lexicon, right down to the body, through the geometric mesh of textiles or the ritualistic paintings covering the skin.

Detail of the Chakana’s representation on Incan wall. Courtesy of LiMac.

Centuries later, another socio-spatial logic was imposed by Spanish colonizers to this holistic symbolic-spatial of geometry. In spite of the formal similarities to the pre-Columbian matrix, the western grid, used in the design of their new cities, spatialized an impetus towards the future and enforced the human ‘order’ before the ‘chaos’ of nature and of the pre-existing historical narratives. This grid was one of the tools for a wider transculturation strategy, which acted through a direct intervention in space resulting in a series of violent infringements to the (social and individual) body’s tacit knowledge. This system also made notions of land ownership tangible and emphasized the public-private dichotomy, introducing ways of understanding reality that were contrary to those of the indigenous populations. Such modus operandi was subsequently repeated in several modernist plans established under another set of global principles, which reaffirmed the grid as a means for applying a rational logic of serialization and standardization of spaces, products and forms of life.

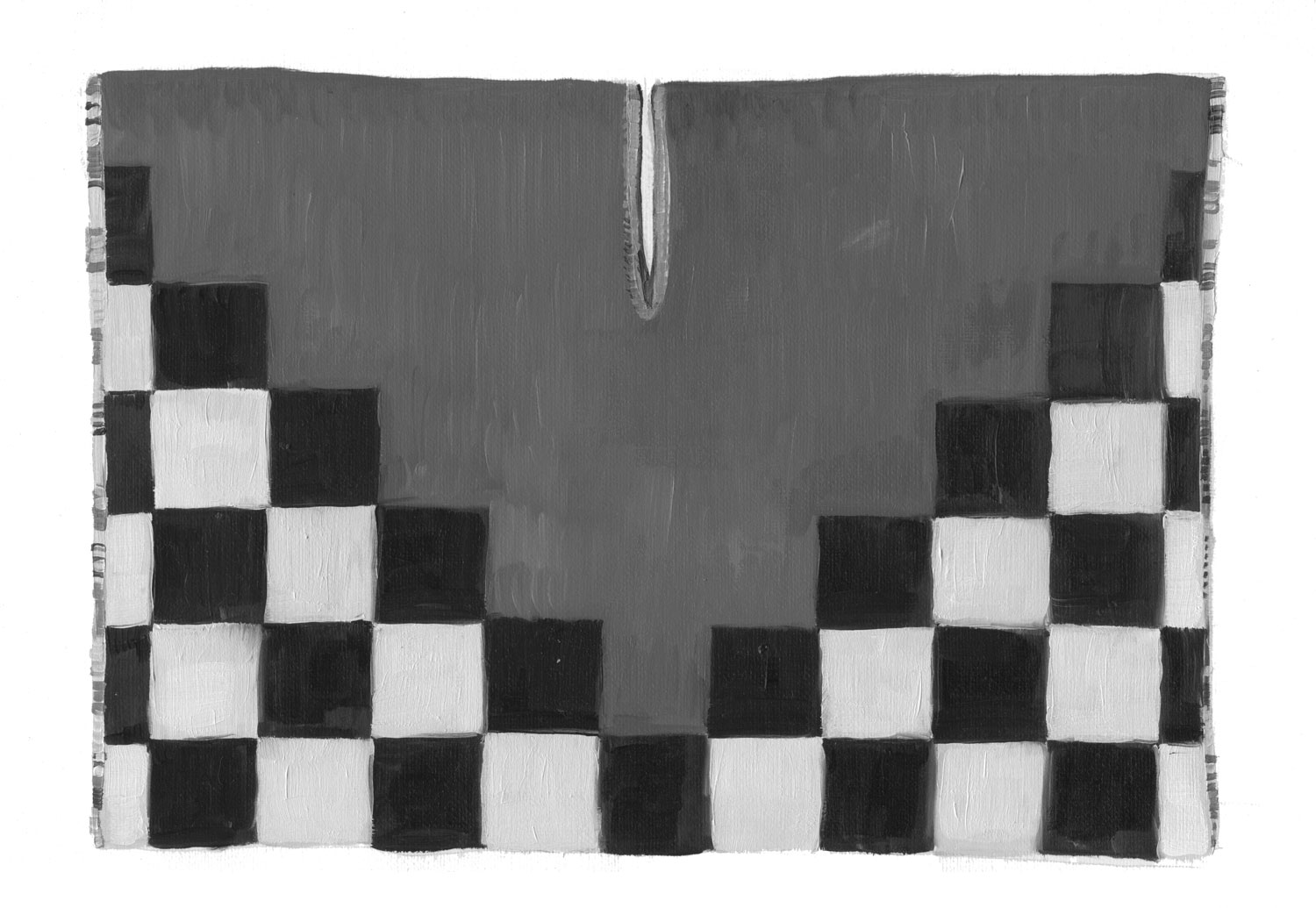

Unku or Inca shirt with stepped pattern. Courtesy of LiMac.

The grid has continually transcended its architectural condition and affirmed itself as a fundamental tool for human cognition, which has had a profound effect on our visual and spatial culture. In a limbo between being a tool for understanding the world and an active instrument for its construction, this geometric system is also a cultural structure, built by both scientific and measurable procedures as well as spiritual, political or moral positions. It is a symbolic-spatial mechanism adapted to the needs and interests of those who produce it and consequently determines the wider scripts of everyday life, nurturing or thwarting specific worldviews.

Geometric body painting of the indigenous tribe Karajá. Courtesy of LiMac.

Curatorial text for SITU #5, Cielo Raso by Sandra Gamarra, Galeria Leme, São Paulo.