Diagram for Attack

closeDiagram for Attack (or how to explain Gerstmann syndrome for rabbits and ducks)1

The medical collection exhibited at the museum of the Central Hospital of the Holy House of Mercy of São Paulo (Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo), hosts clinical and surgical instruments which belong to the long history of this health institution. These items coexist with an illustration that depicts the attack against the president of Brazil in 1897, Prudente de Moraes. Concurrently, the exhibition space at Galeria Jaqueline Martins exhibits a series of objects whose choice and composition derive from an analysis of this illustration. Both spaces are organized according to complementary exhibition logics and the objects presented in each have formal, symbolic and/or semantic correspondents with the items in the other space. These correspondences are expanded by the information compiled in a dossier available in the Hospital Museum.

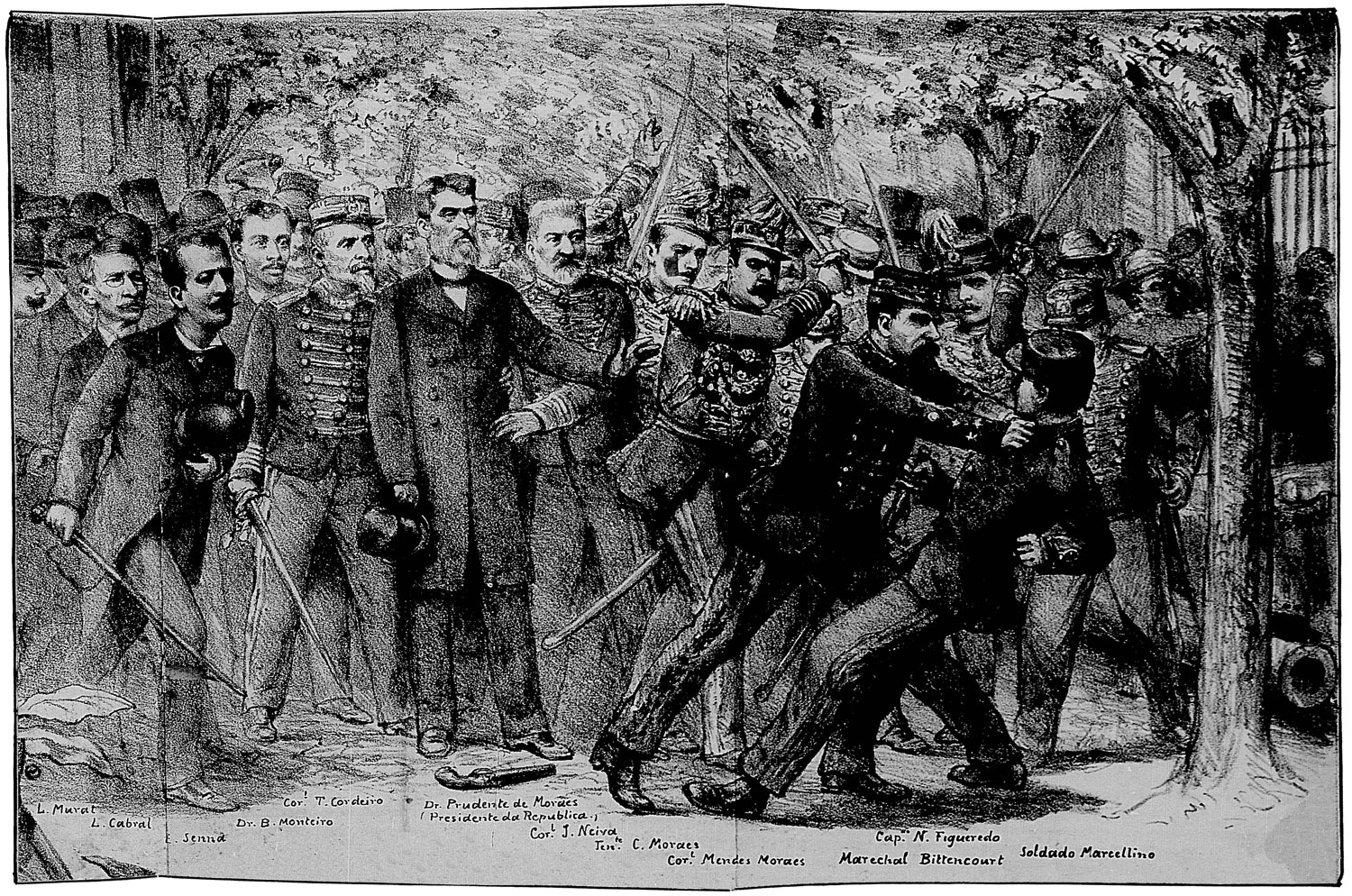

Illustration by Angelo Agostini in the Brazilian newspaper Don Quixote, 1897.

The only image depicting the attempted assassination of Prudente de Moraes – Brazil’s first president elected by direct vote, and the first civilian to take on such position2 – is a hand-drawn illustration published in a newspaper of political satire of the time3. This drawing shows a military ceremony in Rio de Janeiro, on 5 November 1897, in which the president welcomed the victorious battalions returning from the recently completed Canudos War. Out of the blue, the soldier Marcelino Bispo de Melo came out of the crowd and charged at Prudente de Moraes, aiming a revolver at his chest. Melo pressed the trigger a few times but the weapon inexplicably failed. The story goes that the president slowly turned away the offender’s armed hand with his top-hat, like a magic trick. In the meantime, the aggressor was quickly seized by members of the presidential entourage but still managed to pull out a dagger and charge once more towards the president, only to end up mistakenly and fatally striking the Minister of War, Machado Bittencourt, who was protecting Prudente de Moraes. The president escaped unharmed and the attacker was arrested and later found dead, by hanging, in his jail cell. It was conjectured that he was only a piece of a larger political conspiracy, headed by then vice-president Manuel Vitorino Pereira. After the attack, Prudente de Moraes decreed a state of siege, which allowed him to suspend constitutional rights, neutralize political opposition and ensure the predominance of the interests of the coffee-producing oligarchy in national politics.

Deyson Gilbert & Leopoldo Ponce, Diagram for Attack, 2018, Galeria Jaqueline Martins & museum of the Hospital of the Holy House of Mercy. Photos by Filipe Berndt.

A reproduction of the illustration portraying this attack is subtly placed, by artists Deyson Gilbert and Leopoldo Ponce, inside the medical collection room, in an x-ray machine from 1920, which belongs to the hospital’s collection. In x-ray imaging plates, the internal structures of a body appear superposed in two-dimensional planes. Even though x-rays reveal what is concealed, the juxtaposition of body parts still hides certain relations between them. The artists’ incursion beyond what is visible in this historical illustration emphasizes its obscured narratives. This exploration unfolds through the combination of two spaces and through the correlation of the artifacts exhibited in each of them: on the one hand, the medical collection of the Santa Casa Museum which hosts a group of items intended for the preservation of human life and health, and on the other hand, the gallery space of Galeria Jaqueline Martins which exhibits a series of pieces that go-beyond practical use and fixed meanings.

The medical equipment of the hospital’s collection not only recounts the memory of this institution but also illustrates the relationship between Man, Science, and technology. Ideas of ‘truth’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘scientific rigor’ exude from the classificatory and consistent organization that controls the disposition of the equipment in the room. A system of labels and entries serve as mediator between the things and the viewers, guiding their interpretation and mitigating the opacity of medical discourse. The exhibited artifacts have their functions firmly defined from the objective, neutral and universal codes of yesteryear’s medical conventions. Paradoxically, the current connotations of some objects are no longer secured, since the peculiarity of their forms, and their current state of obsolescence, makes way for countless other interpretations and associations that escape the scientific purposes that determined their shapes in the first place.

The objects exhibited in Galeria Jaqueline Martins, insinuate formal and symbolic connections both to key-elements drawn in the illustration, as well as to the equipment shown in the medical collection. The subjects, objects and actions represented in the illustration are cited through the combination of recognizable images with other elements whose meanings are unspecified. The texts that stand between the objects and the viewer avoid prescriptive explanations. Things and their associations do not seek fixed meanings nor are they guided by objective parameters. Nevertheless, their presence in an art gallery affiliates them to a series of art-historical conventions that were once legitimized. The formal characteristics and internal logic of each element, as well as the overall organizational strategy of the ensemble, have spatial and formal correspondences with the Museum's medical collection room. The mental juxtaposition of both spaces opens-up ways of ‘seeing-beyond’ the narratives given by the illustration of the attack against Prudente de Moraes.

The correlations between space and their things, belonging to seemingly disconnected times and themes, trigger a myriad of associations which: revisit ‘official history’ and the collective social imaginary; allude to popular beliefs and myths as well as to the canons of Art History; cite scientific rigor but also border the occult; expose certain subjects while masking others, all in all opening a space of reflection and speculation upon situations where causal relations cannot be demonstrated in strictly objective or factual ways. Situations and relations that are excluded from official narratives, scientific compendia, positivist historiography, and from the growing societal polarization. These find particular frictions and further connotations in relation to the on-going socio-political climate in Brazil, in the aftermath of president Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment, during the interim-presidency of her vice Michel Temer, and in the eminence of Jair Bolsonaro’s tenure.

The desire to ‘see-beyond’ lies in the genesis of various medical and scientific devices, but the projective and subjective capabilities of vision escape the diagnosis of the ophthalmological paraphernalia that predominates in the museum’s medical collection.4 The cognitive phenomena of perception such as the ability to see forms or messages in places where they were not intentionally inscribed, or to discern patterns, meanings, and connections in seemingly random configurations, have for centuries been considered by medical science to be losses of contact with reality, symptoms of psychosis, or other mental pathologies. Such interpretations beyond the meaning of the actual images can occur in physically and mentally healthy individuals, and lead them to believe in hypothesis that come to be understood as truth without any objective verification.5 On the other hand, these interpretations beyond socially-agreed meanings can also allow for strategies to generate critical alternatives to the prevailing schemes within a given context. Since every critique of current conditions depends on the basic premise that reality might be different, how can such interpretive projections of perceptions be developed as part of an effective and affective engagement? Where and how can one nourish the capacity to see beyond what we are supposed to see? How does one bring about a deliberately ‘oblique’ way of looking? And what are its consequences?6

Deyson Gilbert & Leopoldo Ponce, Diagram for Attack, 2018, Galeria Jaqueline Martins & museum of the Hospital of the Holy House of Mercy. Photos by Filipe Berndt.

Perhaps one day we will know that there wasn't any art but only medicine.7

Curatorial text for Diagram for Attack by Deyson Gilbert and Leopoldo Ponce, part of the project 1:1, Galeria Jaqueline Martins, São Paulo.

-

Gerstmann syndrome is a neurological disorder characterized by four main symptoms: difficulty in expressing oneself through writing; difficulty in understanding mathematics; inability to distinguish the fingers from the hands and the disorientation in relation to the left and right / The illusion of the duck-rabbit is an ambiguous image that sometimes looks like a duck or a rabbit. Its first version was published in the German humor magazine Fliegende Blatter (Oct. 23, 1892, p.147)

-

Moraes represented the rise of the coffee-growing oligarchy and of the civilian politicians to the national power after a period of military domination of the executive power.

-

Don Quixote (1895-1903) was an illustrated Brazilian newspaper edited and illustrated by Angelo Agostini.

-

Among them are: a device used to photograph the back of the eye (beginning of the 20th century); electromagnet for extraction of metal debris from the eyeball; amblioscope to measure the angle of a strabismus (1953), among others.

-

Resulting, for example, in the creation of superstitions, beliefs in the paranormal, in the formation of religious structures, conspiracy theories, among others.

-

Amelia Groom, "What might this be?" in De Appel Reads #8, De Appel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018

-

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio. Haï, Éditions Albert Skira, Switzerland, 1971.