Historico-spatial matrixes of inequity

closeIn the seventeenth century, the Portuguese settler Afonso Sardinha assembled the first sugarcane mill of the village of São Paulo, in what was then called the Ubatatá farm, the region currently known as Butantã. Although it seems like an inconsequential fact for the development of the city, the emergence of this kind of engine foreshadows the formation of a specific set of relations between power and land ownership, which precedes what would be the structuring model of the Brazilian territory over the last centuries.

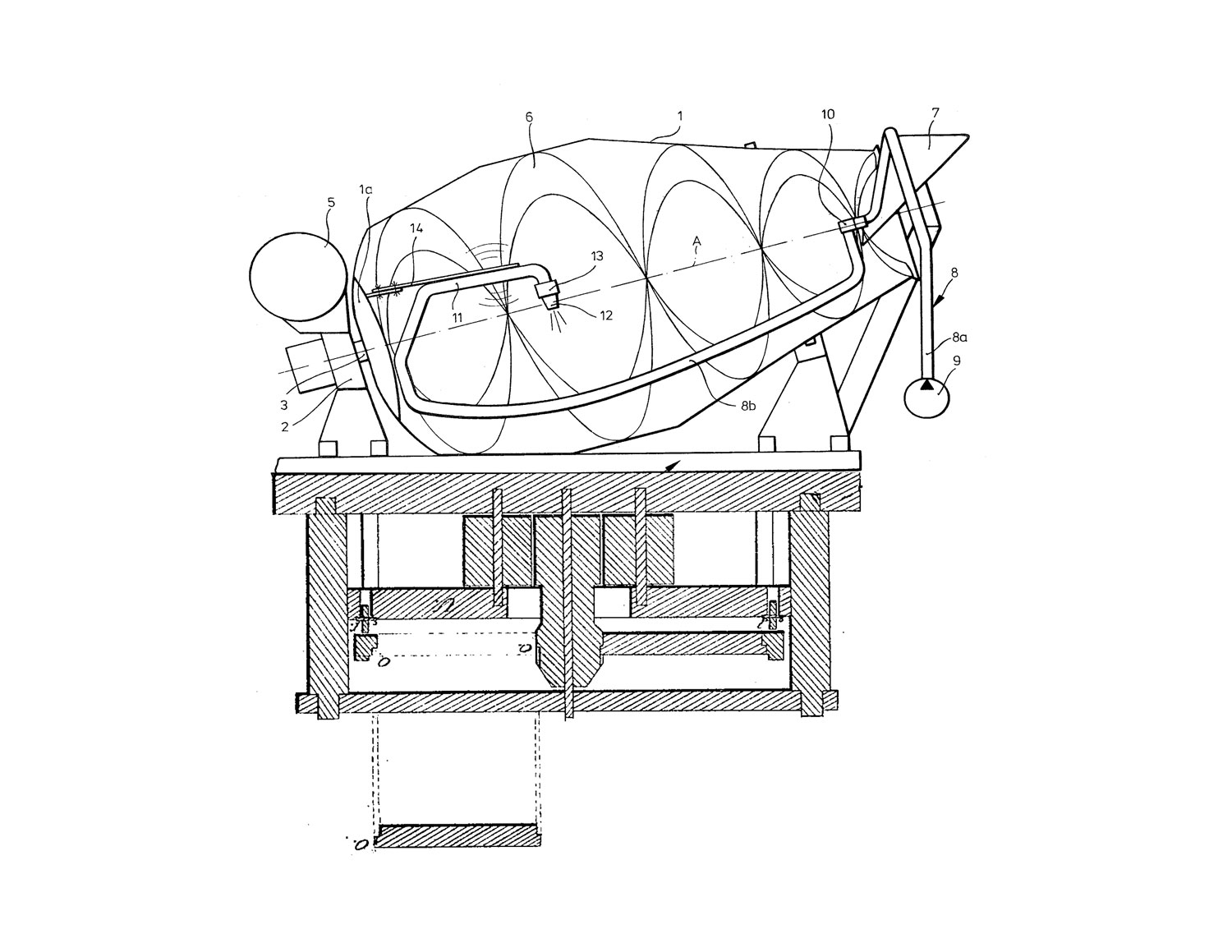

Concrete-mixer and sugarcane mill. Image by Beto Shwafaty, 2016

The cultivation and processing of sugarcane was Brazil’s main colonial ‘industry’ between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. It marked a new and important period in the country’s colonization because it benefited from the strategic combination between the extensive plantations required by sugarcane, and the strategy for dominating and populating the territory, which was rooted in the Royal donation of large portions of land to a handful of Portuguese settlers. This connection not only proved to be successful for the commercial interests of the time, but also favored the strengthening of the latifundia model, privately owned agricultural estates specializing in monoculture destined for export.

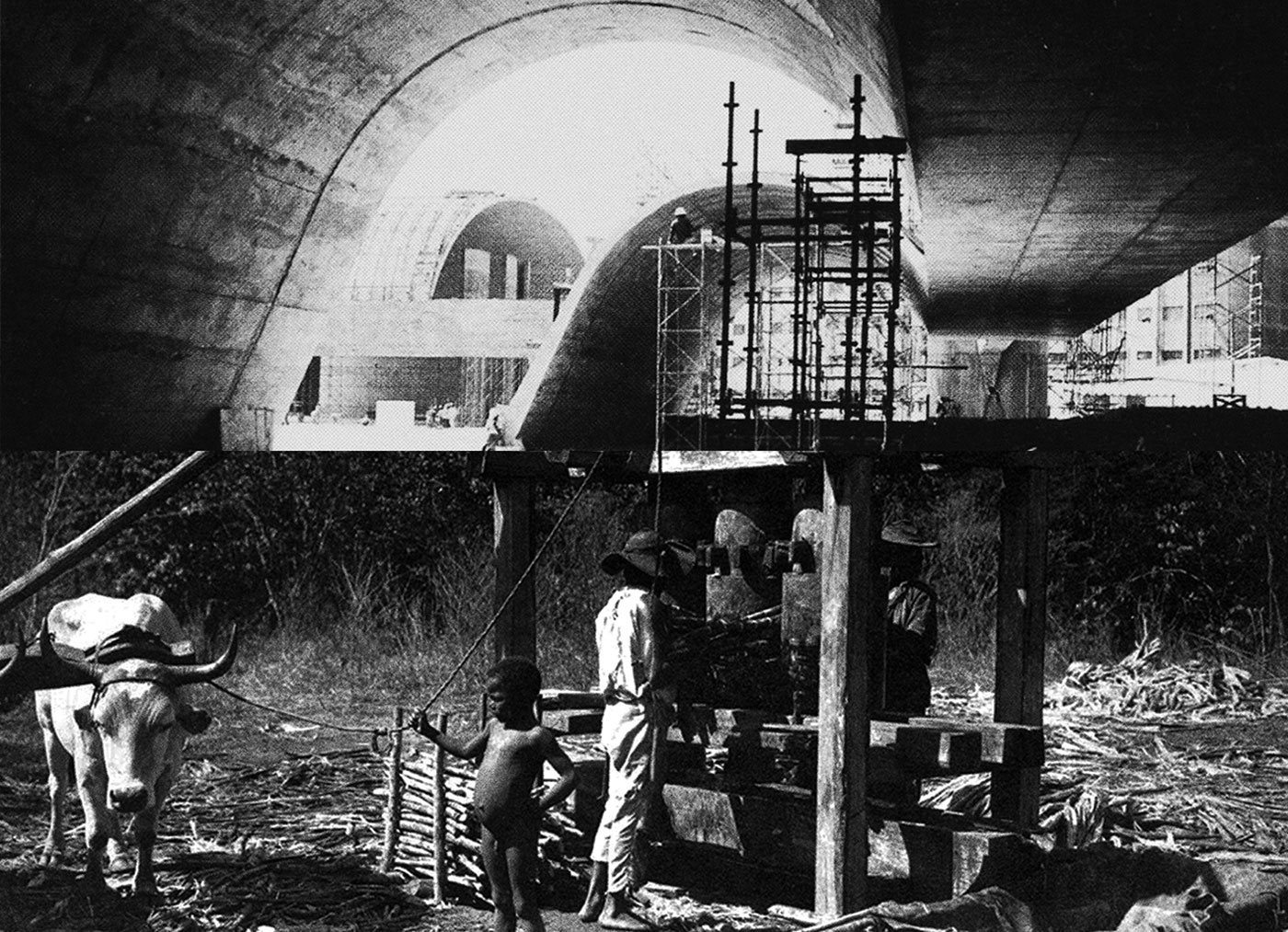

Photomontage: Sugarcane mill in Fazenda do Serrote, Piaui, Brazil, 1912, and the construction of the Latin American Memorial, architecture by Oscar Niemeyer, São Paulo, Brazil, 1988-89. Image by Beto Shwafaty, 2016

The latifundia type of plantation was more than a large portion of land or a strategic farming-system, it was also a system of socio-spatial domination that provided a solid basis of power for the plantation-owners. These had full sovereignty over the domestic, social, political and economic spheres in their lands. An authority which prevented the formation of any intermediate classes that were not directly linked to them or to the agricultural production they monopolized. The power of this small landowning elite was spatialized in the dichotomy between the big-house and the slave-quarters.1 It was also reiterated by the presence of the sugarcane mill as a symbol of slave labor and as the trigger for the intensification of the Atlantic slave trade, which consequentially consolidated a vast underprivileged social base in Brazil.

Photomontage: Sugarcane mill in Fazenda do Serrote, Piaui, Brazil, 1912, and the construction of the Latin American Memorial, architecture by Oscar Niemeyer, São Paulo, Brazil, 1988-89. Image by Beto Shwafaty, 2016

Even though this land tenure matrix may seem distant in time, centuries of history and numerous political changes in the country were not enough to appease its disorders, much less the traces of the patriarchal and slaveholding social formation it established. The successive laws that were created over the years, towards an agrarian reform, strategically ended up reiterating the existing privileges and injustices around the ownership and distribution of land. Official discourses have continually neglected the expropriating and excluding character of the latifundia model of land tenure and its resulting socio-spatial formation. Instead, official narratives glorify its profitable character, and under the designation of agribusiness, there has been a consolidation of the modern latifundia of large (multi)national companies, agro-industrial and stockbreeding enterprises.

Beto Shwafaty, Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories), 2016, sugarcane mill, electric motor, loudspeaker and audio, variable dimensions, Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Filipe Berndt

Through these processes Brazil moved from a predominantly rural to an urban country in a short interval of half a century. But the legacy of this secular economic development has also left its marks in cities. The historic landowning monopoly motivated the migration of a large number of rural workers and poor population to the metropolises, which did not have the adequate infrastructure to receive such intense population fluxes. This triggered complications that persevere until today, such as: the exponential growth of slums and illegal settlements; the lack of control over the use and occupation of the city; the clash between the interests of the real estate market and meager housing, resulting in the constant attempt to move poorer populations away from valuable areas, also pushing them away from the city’s services, facilities and infrastructure, among other factors.

Beto Shwafaty, Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories), 2016, sugarcane mill, electric motor, loudspeaker and audio, variable dimensions, Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Filipe Berndt

Such forces are the result of a patrimonialist2 society whose political, economic and social power still remains concentrated in the hands of an elite. A group whose political clientelism remains strong, allowing them to act as owners of portions of the city and challenge every kind of impersonal and coherent planning. Space, from the territorial to the domestic scale, has been a central tool for this self-perpetuating system of classist and racist hierarchy, which guarantees the maintenance of a strong socio-spatial segregation. The fetish of equality, which has been recurrently sold and consumed in Brazil, conceals an extreme social polarization that becomes even more palpable in times of sociopolitical eruption. Then, one can see the traces of a deeply unequal socioeconomic configuration continuously (re)founded in new kinds of slavery and in a secular subjection to the world market.

Beto Shwafaty, Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories), 2016, sugarcane mill, electric motor, loudspeaker and audio, variable dimensions, Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Bruno Alves de Almeida

Curatorial text for SITU #4, The Phantom Matrix (Old Structures, New Glories) by Beto Shwafaty, Galeria Leme, São Paulo.

-

Translated in Portuguese to casa grande (big house) and senzala (slave quarters) an expression which alludes to the book The Masters and the Slaves by Gilberto Freyre.

-

Patrimonialism is a form of governance in which all power flows directly from the leader, with no distinction between the public and private domains.