The Jan van Eyck’s Stone of Folly

closeDifferent identities have been embodied, distinctive conceptual stances have been enacted, policies have transformed along with outer social, economic, political and cultural reconfigurations, but the cyclic and ever-renewing influx of individuals who are welcomed to the Jan van Eyck Academie has been the binding-thread of the institution’s several characters since 1948. Over the last years, “residents” are referred to as “participants,” and are not just given time, space and expertise, but are also incited to engage with each other, with different advisors and guests, and with the institution’s inner-gears and community. Self-reflection, peer-exchange and collaboration are values that overflow the studio spaces into the entirety of the Jan van Eyck Academie’s inner-workings. The residency is nourished by the entanglement with the institution’s different departments, that also spearhead projects and research within their own directions, bringing to the Academie a rich influx of content, and also taking the institution’s mission outward by connecting it to different communities and partners.1 This inside-out porosity is further enhanced by the institution’s public programme which creates additional intersections between all of these internal and external facets and agents. Such “multiform”2 identity and modus-operandi make the Jan van Eyck Academie hospitable to the diverse and ever-changing characters and intellects that it hosts, and also agile in the responses to an ever-shifting outer-world.

Different logos of the Jan van Eyck Academie over the years.

Now, under Hicham Khalidi’s directorship, initiated in October 2018, the Academie is gradually entering yet a new phase, one marked by a commitment to mobilising the institution’s plurality towards a specific focus. The ambition is to explore how this post-academy for art, design and reflection can contribute to the discussion and action concerning the current environmental crisis, and its manifold effects. This new mission specifically draws on the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C, published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which targets at 2030 as the year until when our societies can cut CO2 emissions, and remain below one and a half degrees of global warming. If this is not achieved by 2030, there will be severe impacts on ecosystems, human health and well-being, likely leaving the effects of climate breakdown irreversible, no matter what measures have been subsequently taken. Aligned with this target, Hicham has put forward a 10-year policy plan which will run in parallel to the IPCC’s countdown, and test how the Jan van Eyck Academie can contribute to such urgent undertaking.

Jan van Eyck Academie's main entrance with site-specific installation by Yona Lee.

2020 marks the start of this decade-long pathway. It also marks the start of my work at the Academie as the new curator and resident liaison. I arrived two months ago (February), exactly when the new policy plan was released. I am now writing this text while in self-imposed quarantine due to the pandemic outbreak of the virus COVID-19. Baptism by fire. This retreat, and the radical readjustment of the institution’s functioning, plans and calendar, coincides with our on-going work on conceptualising the Jan van Eyck Academie’s new mission statement, future public programme, along with the definition of many other aspects of the Academie under this recently started chapter. 3 Such material will feed the institution’s new website, to be launched later this year, crowning the Jan van Eyck Academie’s visual and conceptual rebranding. There couldn’t have been a timelier moment to reflect on, and communicate, this new institutional direction. The urgency expressed in the policy plan has exceeded theory and rhetoric and became tangible in the here-and-now. The impossibility of “business as usual” opens the opportunity for a shift within the institutional identity beyond a mere visual rebranding. It has become globally evident that our everyday life is inextricably linked to a more comprehensive ecosystem, which we can no longer see as an external or independent background for us to endlessly exploit. The current pandemic has also made us aware of the impossibility to rush hurried and simplified responses to processes marked by vast time-space scale, uncertainty and impermanence. The delay between cause and consequence allows us to perceive the true magnitude of the problem when it is already too late. Symptoms appear days after the contagion, and the virus itself has to be considered within wider processes of ecosystemic devastation that humanity already exceeded some time ago. The current state of urgency paradoxically demands for systemic-thinking and the embracing of complexity, opacity and delay, which are at the core of creative, innovative and speculative practices. But what contribution can the arts and design make to this complex social issue? What practical and moral consequences does climate urgency present for artistic practices and the operation of the Jan van Eyck Academie’s residency? Does it threaten the participant's autonomy if the Academie takes these challenges as guidelines for its programme and organisation?4 These are some of the questions that fuel the lively debate within the institution around the Jan van Eyck Academie’s new commitment.5

The JvE´s new logo in the main facade.

Through the balance between its multidisciplinary residency, the sub-institutes and public programme, the Academie is able to nurture a productive correlation between “taking time” and “running out of time”, by on the one hand embracing the notion of “delay” and nurturing the emergence of the “not-yet” by giving time and space for creative practices of all sorts. On the other, by reflecting on and responding to states of emergency of the “here-and-now” through its public-facing commitment, programme and network. The institution’s new focus is instrumental in achieving a prolific correlation between both sides, but only when understood beyond a “theme” that is imposed onto a heterogeneous entity. Instead, it should be understood as a “vector” that bestows a certain direction upon this multiform institute. But this directionality is not intended to trail a one-way road towards a prescribed end. Indeed, the notion of vector, beyond its definition within the realms of physics and mathematics, also refers, in biology, to an agent that carries and transmits a contagious pathogen onto other organisms. No pun intended. The process of contamination is multidirectional, and, in the light of authors such as Anna Tsing, it stands for collaboration, mutual entanglement and interchangeability, diversity instead of purity, and is ultimately a process of survival.6 Understood as a “vector of transmission” the Jan van Eyck Academie’s mission enables the spreading of a shared condition that modifies the agents it comes in contact with, while manifesting itself distinctively in relation to each individual’s organism. It creates a common-ground that is malleable enough to adapt to the different subjectivities, and yet robust enough to uphold a shared denominator across collective negotiations. In this respect, the Jan van Eyck Academie’s strategy of having a succession of annual research throughout the 10-year trajectory allows it to continuously question the topics and strategies that it needs to embrace in order to recalibrate the balance between focus and diversity. While remaining rooted in the overall institutional effort, the mutually-informing research focuses may nevertheless ramify in different directions, constructing an extended enquiry that exceeds the duration and terms of any one particular project, and thus ensuring that the overall programme upholds multiplicity but doesn’t simply become the sum of its parts.

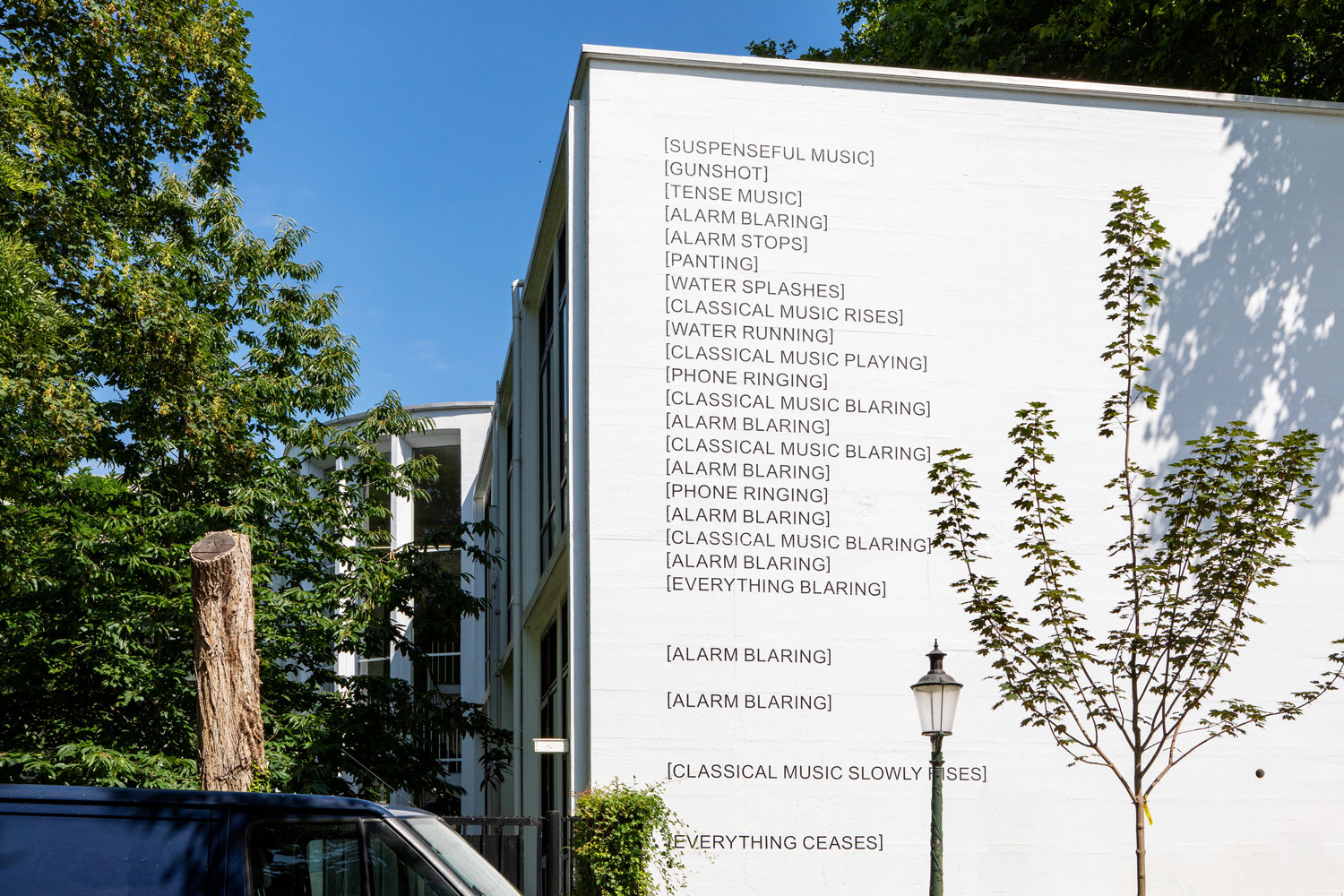

Site-specific installation by Berkay Tuncay on the JvE facade, 2022- on going.

Contamination not only reverberates outward, it also implies profound psychological and physiological shifts within. The ambition to transcend the institution’s mission as a theme also means an alteration of the Jan van Eyck Academie’s own self-understanding and modus-operandi through the embodiment of the values it champions as institutional procedures, spanning from practical aspects (food consumed, sources of energy, modes of travel, etc), to the consideration of both the infrastructures and values fuelling and conditioning its protocols (funding models, organisational structures, the terms of inclusion and exclusion, etc). Efforts are being made to implement more sustainable ways in which the Jan van Eyck Academie can think and work. They range from practical strategies such as reducing the institution’s ecological footprint (by making the building more energy efficient, rethinking the modes of mobility, and others), to content-based initiatives such as the “New Materials Library” (which provides and develops ecological art materials) and the re-thinking of other residency formats exploring cross-sectoral partnerships, among others.

Niina Tervo and Youngeun Sohn, Dinner in the Forest Garden, 2020, part of the Environmental Identities series, Jan van Eyck Academie.

One of the first steps towards communicating the Academie’s renewed mission as well as setting in motion a shift in the institution’s self-understanding is the launch of its new visual identity. Designed by Atelier Brenda (Nana Esi and Sophie Keij) the new identity combines their reflection on the institution’s policy plan, with their lived-experience as participants of a short-term residency at the Jan van Eyck Academie. What most struck Esi and Keij during their residence in the Academie was the quasi-tangible passage of time within the institution, on the one side, emphasised by the cyclicity of the yearly coming-and-going of participants, and on the other, through the distinctive way in which sun-light traverses the Jan van Eyck Academie’s modernist building. The play of light and shadows turns the building into a giant sundial, as if it were responding to the same circadian rhythms that tie living bodies to the cycles of the natural world. Light and Time became the central elements of the identity, and were visually synthesised in the interplay with stylised sundials, orbits, cycles, shadows and other motifs that convey the passage of time, conjoining seemingly irreconcilable notions such as “taking time” and “running out of time.” Time is also a synonym for Weather in languages such as Portuguese (tempo) and French (temps). By visually and conceptually connecting these several layers of meaning, the identity expresses the Academie’s new ambition to create a stronger entanglement between its inner “cycles” with those of the outside world, particularly through a heightened sensitivity towards environmental changes.

Explanatory scheme of the JvE logo designed by Atelier Brenda.

This entanglement is not only a conceptual stance, in fact, such sensitivity is already embedded in our own bodies. Most living organisms have "built-in" and self-sustained circadian rhythms, which consist of physical, mental, and behavioural changes that are incited by environmental cues such as light and temperature. This sensitivity to external factors is calibrated by a complex “biological clock”, within which the pineal gland plays a key role by producing melatonin as a response to the light the eyes perceive, thus keeping humans awake, or inversely, inducing tiredness. Beyond influencing sleep-wake cycles, circadian rhythms also have a wider impact on many other bodily functions such as hormone production, eating habits, body temperature, and brainwave activity. The correlation between human physiology and psychology with a set of external stimuli has long been subjected to scientific study, and also to much mythological and philosophical speculation, particularly before the pineal gland was scientifically understood as an endocrine organ. Descartes proposed that this gland was the point of mediation between the body and the soul, and controlled the communication between the physical body and its surroundings. The notion of "pineal-eye" was also central to Bataille’s philosophy, who uses it as an allusion to the blind-spot in Western rationality and an organ of excess and delirium.7 The “pineal-eye” was even assumed to be atrace of the "third-eye”, an organ of the "sixth" sense, with the ability to see into higher realms of existence and consciousness. The mysterious and exoteric aura of this organ has, since Classical Antiquity, also granted a connection to mental disorders and legends about the “stone of folly”. This hypothetical stone, located inside an individual's head, was thought to be the cause of madness, and it was believed that its surgical extraction might be the cure for “folly”. Although it is very unlikely that these operations were ever performed, they were immortalised in several paintings, such as Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Stone Operation” (1488), which can be read both as an allegory of foolishness as well as a satire of scientific knowledge, deconstructing the moralising tenor of its time through an interplay between science and myth, “fact” and fiction.

Site-specific installation by David Habets, 2021.

“The real must be fictionalised in order to be thought,” states Ranciére,8 but is fictionalisation enough whilst living through a profound mutation in our relation to the world? The unfolding pandemic triggered alterations spanning from the reconsideration of basic forms of social conduct and intimacy, to the reassessment of planetary movements and modes of governance. We seem to be fluctuating between a “new normal” and the “normalisation of the pathological.” Indeed, when Bruno Latour uses the expression “a profound mutation in our relation to the world,” he is not only describing the ongoing exacerbation of the “ecological crisis”, but also establishing a parallel to the scholarly definition of madness.9 The correlation between environmental oscillations and radical changes in self and social identity is further captured by the myth of the “stone of folly,” as a hypothetical mutation in the organ that calibrates our sensitivity to environmental cues. The pineal gland sits right between the human brain’s two hemispheres: the left, which performs analytical and logical thought, and the right hemisphere, which performs intuitive and creative thought. The Jan van Eyck Academie’s ambition towards a heightened responsiveness to environmental change, followed by a shift in its identity, could point to a figurative reconnection with its “stone of folly”. This symbolic hypothesis is not to be understood as a reiteration of associations between “madness” and “creative genius”, nor as a romanticisation of mental illness, which can be a debilitating condition. Instead, it is an attempt to go deeper in the understanding of what the Academie’s ambition actually entails. What could it mean for the institution to embody a condition of deviance, an intrinsic resistance to returning to the previous “pathological-normality”, and a strategy of responding to the current “altered state” of global life? A condition that both triggers and nurtures thinking in unprecedented ways, unsettling seemingly stable binaries between left and right, analytical and creative, “self” and “non-self”. A condition that brings to light “knowledges” and modes of expression that do not find a space of resonance within traditional institutions, canonical forms of display, or conventional domains of academia. A condition marked by a radical embodiment of alterity, that would not only address the “disconnect between old definitions of humanity and what humans must now confront” but also foster “as many definitions of humanity as there are ways of belonging to the world”.10 A condition that would not only point to another reality, but prefiguratively personify the modes of organisation and social relationships of a just and sustainable society-to-come. Deviance is always culturally (re)defined and it is no less than the Jan van Eyck Academie’s response-ability to help shape it.

JvE Forest Garden with sculpture by Kanthy Peng, 2021.

Text commissioned by De Appel Amsterdam, for the project Everything is New curated by Nikolai Alutin.

-

The Jan van Eyck Academie’s departments are: Printing & Publishing, Wood & Metal, Photography & Audiovisual, Food, Library, New Materials Lab, Art & Society, Research & Education, and Nature Research. These not only cater to the needs of participants and the institution but also connect the Jan van Eyck Academie to governmental and private institutes, universities, diverse communities of interest, among others. For more information on each department, please visit the institution’s website.

-

The Jan van Eyck Academie was defined as a Multiform institute for fine art, design and reflection under the directorship of Lex ter Braak (from 2011 to 2018), who granted the institute a renewed structure and design. In the light of the effects of the cutbacks and the need to generate its own income, the institution transitioned from a closed studio model into an open and outward-looking post-academy.

-

The process of writing this text happened simultaneous to the conceptualisation of the Jan van Eyck Academie’s public programme and the written contents of its new website. Thus, there are many echoes, spillages and intersections between these different elements.

-

The Jan van Eyck Academie welcomes a variety of practitioners such as artists, designers, architects, curators, writers, fashion designers, chefs, among others working in-between and beyond these categories. The selection of participants is not bound by a direct affiliation to the institution’s focus but by the quality of each practice. Nevertheless, practices that have affinities with the Jan van Eyck Academie’s mission are encouraged to apply.

-

These questions are expressed in the Jan van Eyck Academie’s policy plan, written by its director Hicham Khalidi and titled 2030 - The post academy in a world in transition.

-

How does a gathering become a “happening,” that is, greater than a sum of its parts? One answer is contamination. We are contaminated by our encounters; they change who we are as we make way for others. As contamination changes, world-making projects, mutual worlds – and new directions – may emerge. Everyone carries a history of contamination; purity is not an option. - TSING, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2015, p.27

-

Denis Hollier, Against Architecture. The writings of Georges Bataille, MIT Press, Reissue 1992, pp.115, 116.

-

Jacques Ranciére, The Politics of Aesthetics. The Distribution of the Sensible, Continuum, 2004, p.38.

-

Alas, talking about a “crisis” would be just another way of reassuring ourselves, saying that “this too will pass,” the crisis “will soon be behind us.” If only it were just a crisis! If only it had been just a crisis! The experts tell us we should be talking instead about a “mutation”: we were used to one world; we are now tipping, mutating, into another. (…) As we hear one piece of bad news after another, you might expect us to feel that we had shifted from a mere ecological crisis into what should instead be called a profound mutation in our relation to the world. (…) “An alteration of the relation to the world”: this is the scholarly term for madness. (…) If ecology drives us crazy, it’s because what we call ecology is in effect an alteration of the alteration in our relations with the world. In this respect ecology is both a new form of madness and a new way of struggling against the forms of madness that preceded it. – Excerpts from Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia. Eight lectures on the new climatic regime, pp.7-14.

-

Idem, Ibidem, pp.107, 108.